A Sacred Space

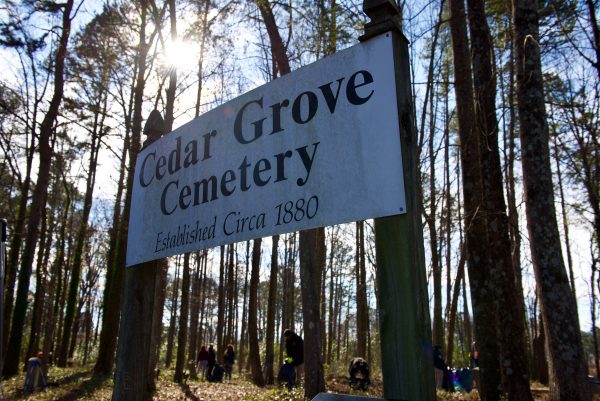

When Kevin Donaldson ’21 first visited Cedar Grove Cemetery last year, he found sunken graves, toppled gravestones, piles of trash and more than 90 trees and tangled vines destroying gravesites.

“There are folks who still come out and visit graves, but someone older likely could not do so safely,” Donaldson said. “At the same time, there was no one to keep those graves maintained either.”

The historic Black cemetery fell into disrepair after the last known owner and caretaker, John Shead Davidson, died in 1972. Despite sporadic cleanups, the ruin always resurfaced. This is the fate of many historic Black cemeteries throughout the nation.

PRESERVING HISTORY

Donaldson, who earned a bachelor’s degree in history and is now completing a master’s in that subject at UNC Charlotte, learned about the cemetery in a museum studies class. Since then, he has felt driven to research — and permanently restore — the neglected 1.8-acre burial ground off Hildebrand Street near Beatties Ford Road.

“As a graduate student of history, I view a cemetery as a museum,” he said, explaining his motivations to undertake the project. “Quite a few military veterans are buried here as well as leaders from the historic Brooklyn community. They are a big part of the city’s history, and it’s a shame to see the place fall into disrepair. The South, unfortunately, is fraught with racial strife and always has been. Having seen this abandoned cemetery, I feel responsible to help in some way.”

Cemeteries are sacred spaces, replete with historical significance and community and family connections. Yet, historic Black cemeteries are often under-resourced, under-documented and can lack consistent care when on remote properties or in marginalized communities, said Angela M. Thorpe, director of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources’ African American Heritage Commission.

“Historically, African American burial practices have been severely restricted,” Thorpe told a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee considering the African-American Burial Grounds Preservation Act, a bill co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. Alma Adams (NC-12).

“Everything from ‘plantation politics’ to legal restrictions have played a role in shaping how, when and where African Americans were buried,” Thorpe said. Also, as African Americans have migrated across the country, land has changed hands, and community landscapes have changed drastically over time, further complicating the issue.

The bipartisan legislation, which has passed a Senate committee review, would establish a National Park Service program to provide grant opportunities and technical assistance to local partners to research, identify, survey and preserve these historic sites.

“We want to tell the stories of our elders who were laid to rest here, so we don’t forget them.”

– Nate Freeman, founder, From One to Some

GATHERING COMMUNITY

Over the past year, Donaldson has built alliances with neighborhood and nonprofit leaders, Charlotte and Mecklenburg County officials, business owners, and academic leaders, faculty and students at UNC Charlotte and Johnson C. Smith University, including members of the UNC Charlotte Graduate History Association.

He has organized cleanup days and enlisted the help of Bartlett Tree Experts and Arborscapes Tree & Landscape Specialists to bring in teams and equipment to remove trees and prepare the site for volunteers to safely clear remaining debris, vines and brush, and map the graves.

The local community had made headway, but the cleanup was daunting,” he said. “It’s really a project for tree experts. I was able to share existing relationships, hoping to help move things forward.”

Despite the clear progress, cleaning up the cemetery is not enough to ensure its future, as previous cleanups have shown. Creating a way to maintain the cemetery, with its estimated 75-150 graves, is essential.

In an important step, Donaldson used his research skills to prepare and submit an application to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission, seeking historic landmark designation. The city of Charlotte provided a grant and completed an official site survey, which Donaldson included in the application. The nonprofit From One to Some, which works in the local neighborhood and school, signed on as the fiscal agent.

Nate Freeman, founder of From One to Some, and his business partner Che´ Abdullah have nurtured community relationships, organized several cleanups and brought on additional partners, including The Brooklyn Collective and Mecklenburg County Park and Recreation Department.

“Building a sense of community fits in with our mission,” Freeman said. “We want people to take a sense of pride in the people who came before us and helped shape this area. The plan is to create trails, historical markers and QR codes so we can bring Cedar Grove back to everyone’s attention. We want to tell the stories of our elders who were laid to rest here, so we don’t forget them.”